Chinese Painting: An Introductory Guide

Painting has been admired and pursued by Chinese people of refined tastes since ancient times. It has become an artistic form to show disposition, express feelings and cultivate sentiments. It was listed as one of the “Four Arts of Chinese Scholars” – the other three are ‘qin’ (the Guqin, Chinese stringed instrument), ‘qi’ (the strategy game of ‘go’), and ‘shu’ (Chinese calligraphy).

Traditional Chinese painting (‘guo hua’) is similar to calligraphy – which itself is considered to be the highest form of painting – and is executed with a brush (made of animal hair) dipped in black ink (made from pine soot and animal glue) or colored ink. Oils are not generally used. The most popular type of media is paper or silk, but some paintings are done on walls or lacquer work. The completed artwork may then be mounted on scrolls, which are hung or rolled up.

Chinese paintings have been influenced by the philosophies of Buddhism, Confucianism, and particularly Taoism, which seeks to show a sense of harmony between humans and the larger world. This allows painters to work their personal feelings and emotions into how they represent a landscape. White space in Chinese painting is intentional to invite viewers to think and interpret the piece for themselves, filling the void with their own imagination and viewing experience.

1. What are the basic media of Chinese Painting?

The basic media of Chinese painting are brush, ink, pigments, and a ground, usually silk or paper. Chinese brushes were made of one or several kinds of animal hair, maybe from animals including rabbit, wolf, goat, badger, and even the whiskers of mice. These brushes are constructed in a special way that allows them to come to a sharp point for fine lines and yet be fat enough for wider strokes. They are capable of holding enough ink for a few long continuous strokes or many short ones.

Ink was made from soot mixed with glue and formed into hard sticks. The finely ground soot produces the color while the glue both holds the stick together and acts as an adhesive to bind the ink to the paper or silk. Pine soot, from the inner wood of the tree, produced the best all-around ink, but other kinds of soot and various animal glues have been used. To use the ink, the stick is rubbed on an ink stone and mixed with water as needed. To save time, many artists also use liquid ink instead.

The pigments used for Chinese painting are made from minerals and plants. Chunks of pigments are crushed and ground into fine powder and then combined with a binding agent such as animal glue. The color strength is controlled by mixing the pigment with shell white, obtained from ground seashells. Nowadays we also use some chemical colors in Chinese painting.

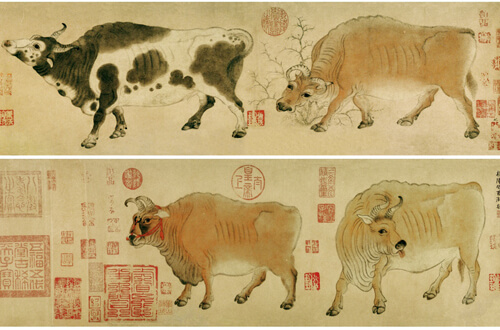

Even though paper was invented in China more than 2000 years ago, it was not widely used for painting until the Tang Dynasty (618-907CE). All the early paintings were painted on silk. The earliest extant painting on paper is Five Oxen, a painting by Han Huang (723-787). It is currently housed at the Palace Museum in Beijing. Since the Tang Dynasty, many artists gradually started painting on Xuan paper, which is also known as rice paper. It originally was made from the bark of the Pteroceltis Tatarinowii tree (a relative of the Elm tree). Xuan paper features great tensile strength, a smooth surface, pure and clean texture and clean strokes, as well as a great resistance to creasing, corrosion, moths and mold. The majority of ancient Chinese books and paintings by famous painters that survived until today are well preserved on Xuan paper.

2. What are the usual subjects of Chinese painting?

There are three main subjects of Chinese painting: human figures, landscapes, and birds and flowers.

Figure paintings can be traced back to the Neolithic era. They were first on pottery, then on tiles, tomb and mural walls, and in family shrines. It became dominant during the Tang Dynasty (618-907CE) under the influence of Buddhism where figure painting is part of the custom.

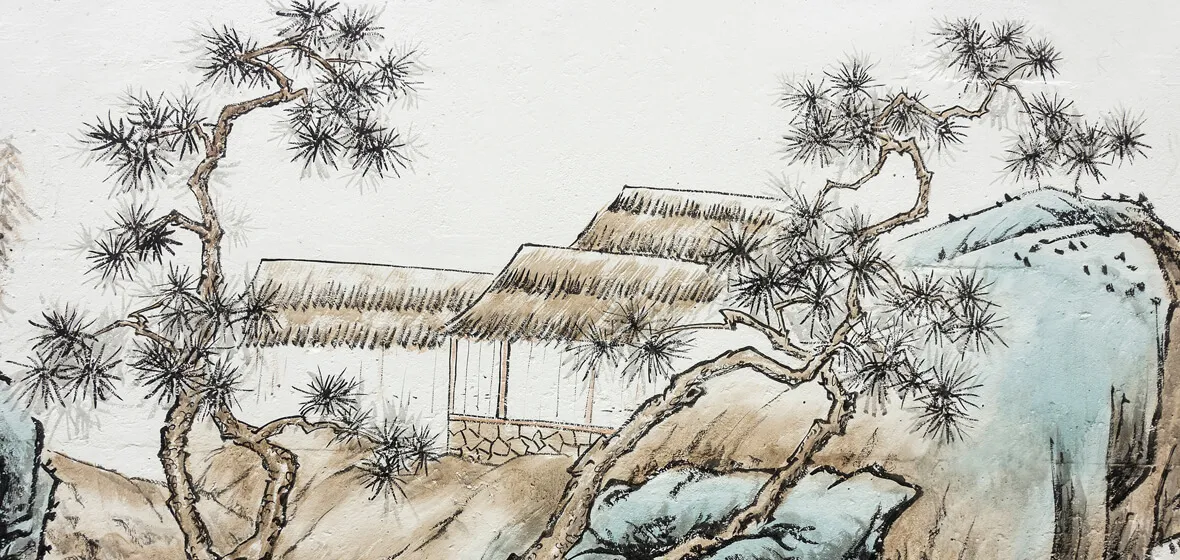

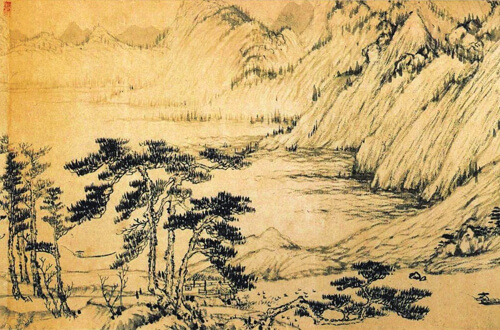

By the late Tang dynasty, landscape painting (山水, shān shuǐ, mountains and water) had evolved into an independent genre that embodied the universal longing of cultivated men to escape their quotidian world to commune with nature. Landscapes strive to achieve a balance between yin, the passive female force, represented by water, and yang, the male element, represented by rocks and mountains.

Paintings of birds, insects, fish, animals and flowers can be traced back to the Shang (1600-1046 BCE) and Zhou (1046-256 BCE) dynasties, when abstract images of birds were engraved on bronze pottery ware. It was during the Wei Kingdom (220-265CE), though, that artists began to specialize in bird-flower painting and made the subject into its own genre. It has been a popular subject since around the time of the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE). The more painstaking techniques are used to give a realistic rendering. Animal subjects are shown in active postures – not a static pose and rarely looking at the painter. These works of art were not merely meant to be depictions of nature; they were also meant to convey abundant symbolism. For example, the lush, full bloom of the peony flower represents wealth and opulence. The Chinese orchid (lan hua), which grows in secluded places and spreads a subtle fragrance, stood for modesty and sometimes for the scholar-official neglected or undervalued by his ruler; the pine and other evergreen trees stood for steadfastness in adversity, and so forth.

3. What are the main formats of Chinese paintings?

There are 5 main formats of Chinese paintings, namely Hanging scroll, Handscrolls, Album leaves, flat oval fans, and standing screen painting.

The hanging scroll typically ranges in height from 55cm (21.6in) to 367 cm (144.5in). The width is from 34cm (13.4in) to 144cm (56.7in). It is meant to be hung on the wall and viewed all at once and can remain on display for extended periods, simply as decoration or as a seasonal and auspicious exhibit.

Handscrolls are typically between 23cm (9 in) and 35cm (13.7in) in height but may vary greatly in length; the famous A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains (千里江山图 qian li jiang shan tu) is 12 m (39.3ft) long. Handscrolls are designed to be unrolled, from right to left, revealing one scene at a time. As each new section is unrolled, the previous scene is rolled up, giving the viewer the feeling of a journey through the landscape.

Album leaves were first used for painting during the Song Dynasty (960-1279); their use likely stems from printing and book binding practice. Albums were quite small and intimate in scale, and often included paintings as well as calligraphy. The paintings and calligraphy usually work together, sometimes with a poem on one page and a small painting illustrating it on a facing page.

Fans: Chinese fans are often decorated with landscapes and calligraphy. The practice of writing or painting on fans can be traced back to the Han dynasty (202BCE-220CE). By the Song dynasty (960-1279 CE) painted circular fans became popular in court circles, and court artists, including emperors, are recorded as having painted these types of fans and they became known as ‘palace fans’.

The last format is the standing screen painting. Standing screens are used as room dividers, a background, or to add privacy. Normally there are 4,6,8 or 10 panels, and the paintings on the screens are of the same subjects, like the scenery of four seasons, or the so called Four Noble Ones: the plum, the orchid, the bamboo, and the chrysanthemum. Some screens, however, have been remounted and preserved as hanging scrolls.

4. What are the two main techniques of traditional Chinese painting?

There were two primary techniques used for ancient Chinese paintings. The first technique is known as Gongbi, which translates to “meticulous”, also known as court-style painting, where artists would capture scenes and figures with very precise and detailed brushstrokes. The results were often saturated in color, depicting a narrative or figurative subjects.

The second technique is Xieyi, which literally means “writing ideas,” and marries the freehand techniques of calligraphy, line drawing, and shading. Unlike Gongbi Painting, Xieyi Painting is designed not to be realistic, but rather capture the spirit of the subject.

5. What are the extant top 10 Chinese paintings?

Chinese paintings are fragile. To appreciate a Chinese painting, you would have to unroll a scroll, and roll it back up. If it were an album, you would have to open it, and turn the pages. Over time, these paintings fall apart. That’s why the extant ancient paintings are so precious.

1. Spring Morning in the Han Palace (汉宫春晓图 han gong chun xiao tu)

- Author: Qiu Ying

- Date Painted: 1540-1544

- Medium: ink and colors on silk

- Size: 30.6 cm x 574.1 cm

- Where it is housed: National Palace Museum, Taipei

2. Emperor Taizong Receiving the Tibetan Envoy (步辇图 bu nian tu)

- Author: Yan Liben

- Date Painted: 640CE

- Medium: ink and color on silk

- Size: 129.6 cm x 38.5 cm

- Where it is housed: Palace Museum, Beijing

3. Nymph of the Luo River by Gu Kaizhi (Song Dynasty Copy) ( 洛神赋图 luo shen fu tu)

- Author: Gu Kaizhi

- Date Painted: c. 1150–1250

- Medium: ink and color on silk

- Size: 24.2 cm x 310.9 cm

- Where it is housed: Palace Museum, Beijing

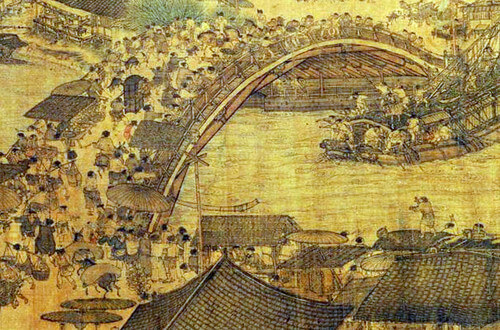

4. Along the River During the Qingming Festival (清明上河图 qing ming shang he tu)

- Author: Zhang Zeduan

- Date Painted: 12th century

- Medium: ink and colors on silk

- Size: 24.8 cm x 528.7 cm

- Where it is housed: Palace Museum, Beijing

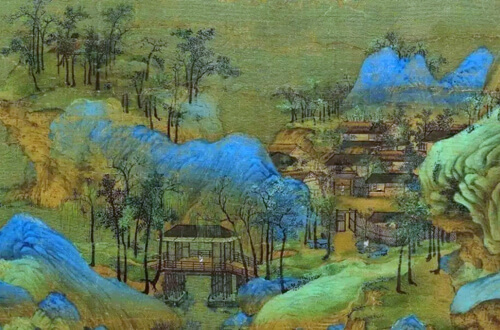

5. A Thousand Li of Rivers and Mountains (千里江山图 qian li jiang shan tu)

- Author: Wang Ximeng

- Date Painted: 12th century

- Medium: ink and color on silk

- Size: 51.5 cm x 1191.5 cm

- Where it is housed: Palace Museum, Beijing

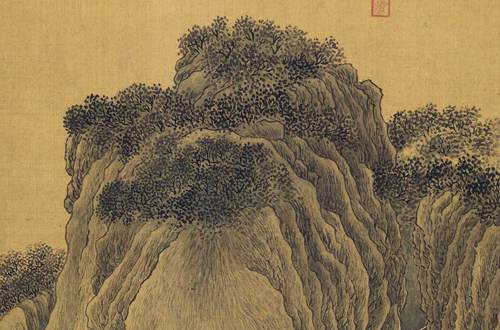

6. Travelers Among Mountains and Streams (溪山行旅图 xi shan hang lü tu)

- Author: Fan Kuan

- Date Painted: 11th century

- Medium: Ink on silk

- Size: 206.3 cm x 103.3 cm

- Where it is housed: National Palace Museum, Taipei

7. Five Oxen (五牛图 wu niu tu)

- Author: Han Huang

- Date Painted: 8th century

- Medium: Ink and color on paper

- Size: 20.8 cm x 139.8 cm

- Where it is housed: Palace Museum, Beijing, China

8. Dwelling in the Fuchun Mountains (富春山居图 fu chun shan ju tu)

The painting was separated into two parts in 1650. The first part, “The Remaining Mountain” is now in the Zhejiang Provincial Museum in Hangzhou while the latter part known as “The Master Wuyong Scroll” is in the National Palace Museum in Taipei. On June 1, 2011, the two pieces were reunited for a time in Taipei.

- Author: Huang Gongwang

- Date Painted: 1350

- Medium: Ink on paper

-

Size:

“The Remaining Mountain,” 31.8 x 51.4 cm

“The Master Wuyong Scroll,” 33 x 636.9 cm -

Where it is housed: “The Remaining Mountain,” in Zhejiang Provincial Museum, Hangzhou

“The Master Wuyong Scroll,” in National Palace Museum, Taipei

9. Night Revels of Han Xizai (韩熙载夜宴图 han xi zai ye yan tu)

- Author: Gu Hongzhong

- Date Painted: 10th century

- Medium: Ink and color on paper

- Size: 28.7 x 335.5 cm

- Where it is housed: Palace Museum, Beijing

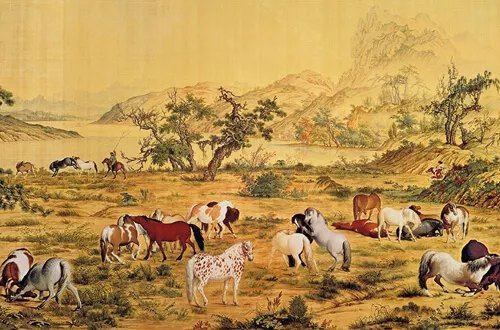

10. One Hundred Horses (百骏图 bai jun tu)

- Author: Giuseppe Castiglione (known as Lang Shining in China)

- Date Painted: 1728

- Medium: ink and colors on silk

- Size: 94.5 x 776.2 cm

- Where it is housed: National Palace Museum, Taipei

The Semi-Cursive Script

The Semi-Cursive Script  Top 20 Chinese Movies

Top 20 Chinese Movies  The History of Chinese Tea

The History of Chinese Tea  Silk Road

Silk Road