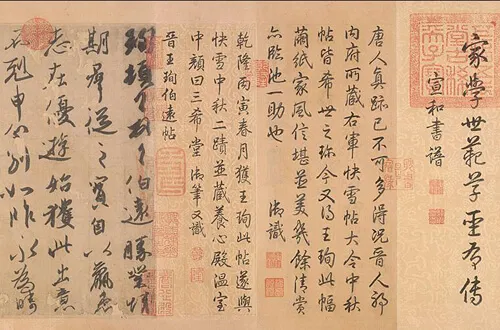

Top 10 Chinese Calligraphy Works You Should not Miss

You can find many beautiful calligraphy works in museums in China and in international museums like the Metropolitan Museum of Art, but the following ten works are regarded as the best of them.

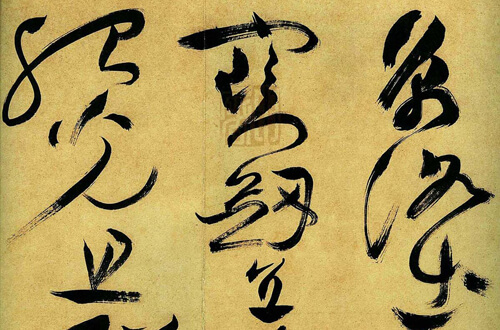

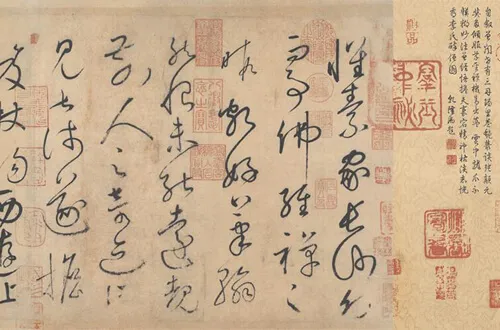

No. 10 Poems in Cursive Script (草书诗帖)

- Author: Zhu Yunming (1461-1527)

- Date written: 15th century

- Script Style: Cursive Script

- Size: 1147.5 x 36.1 cm

- Where it is housed: National Palace Museum in Taipei

Zhu Yunming is an important poet and calligrapher of the Ming Dynasty. He was listed as one of the “four talents of Wuzhong (modern Suzhou)”. The other three are Tang Yin, Wen Zhengming and Xu Zhenqing. An uninhibited, highly creative calligrapher, Zhu is best known for his “wild” cursive script inspired by the Tang dynasty masters Zhang Xu (ca. 700–750) and Huaisu (ca. 735–800) and by the Song scholar-poet Huang Tingjian (1045–1105).

The Poems in Cursive Script included four poems composed by the accomplished poet Cao Zhi from the Three Kingdoms (220-280). The style of this calligraphy work is similar to that of Zhang Xu and Huai Su, but the basic techniques, including the brushwork, stippling, and structure of characters, all reflect a combination of various calligraphy schools since Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi in the 4th century.

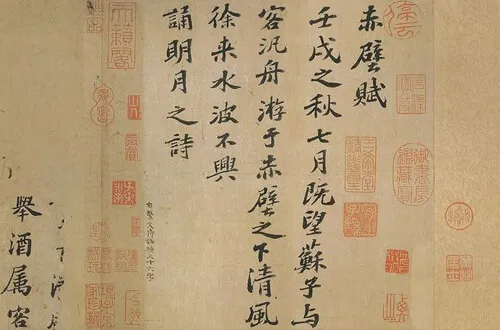

No. 9 Odes to the Red Cliff (前后赤壁赋)

- Author: Zhao Mengfu (1254 – 1322)

- Date written: 1301

- Script Style: Running Script

- Size: 11.1 x 27.2 cm

- Where it is housed: National Palace Museum in Taipei

Zhao Mengfu was a descendant of the royal family of the Song dynasty (960–1279) and had been educated in the imperial university. The Southern Song dynasty (1127– 1279) fell to the conquering foreign Mongolian government when Zhao Mengfu was in his mid-twenties. His decision to serve the new Yuan court a few years later was not made easily and made him a controversial figure in Chinese art history. Nevertheless, he was the preeminent painter and calligrapher of the early Yuan dynasty (1279- 1368), and one of the most versatile and subtle artists in the Chinese tradition. As a leading calligrapher, Zhao advocated a return to ancient models, successfully integrating styles of the Jin (265–420) and Tang (618-907) dynasties to create a new synthesis in both regular and cursive scripts.

Red Cliff was the site of a major battle between the forces of Northern China led by the warlord Cao Cao and the allied defenders of the south under the command of Liu Bei and Sun Quan in 208 CE. Cao Cao was defeated by the southern coalition and driven back north, ending his dream of unifying China under his rule. In 1082, the writer Su Shi (1037-1101) traveled to this historic site and wrote two “Odes to the Red Cliff”, significantly contributing to the annals of Chinese literature. Artists of subsequent dynasties created numerous works to commemorate Su Shi and his odes, including the "Red Cliff" painting and calligraphy works. For calligraphy works, Odes to the Red Cliff by Zhao Mengfu is the most famous. He embodies the essence of calligraphy of earlier generations, particularly benefiting from Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi.

No. 8 Thousand-character Essay in Cursive Script (草书千字文)

- Author: Zhao Ji (1082 – 1135)

- Date written: 1112

- Script Style: Cursive Script

- Size: 1147.5 x 36.1 cm

- Where it is housed: Liaoning Provincial Museum in Shenyang

Zhao Ji, best known as Emperor Huizong of the Song, was not a good emperor, but he was a talented artist. He was good at poetry, painting, calligraphy, and music. His most significant and well-known contributions were to Chinese calligraphy. He even developed his own style, called Slender Gold. It has a twisted quality, like gold filament, and is characterized by thin, sharp strokes and sharp turns and stops. The characters are angular, with chiseled corners. The endings of the horizontal strokes are also unique in that the brush clearly goes back in the opposite direction.

Qian Zi Wen, or Thousand Character Classic, was one of the most popular language primers for schoolchildren in ancient China. It consists of 1,000 unique characters chosen as much for calligraphy practice as for common usage of characters. You can find many Qian Zi Wen masterpieces from famous masters, covering mainstream scripts such as regular script, semi-cursive script, and cursive script and so on. Like other calligraphers, Zhao Ji loved to use Qian Zi Wen for calligraphy practice, but only two pieces are extant, one is in Slender Gold style, and this one is in cursive style. Cursive Style is written without strict guidelines, as each artist writes in his or her own unique way. Some strokes and some characters are linked so that the writing is done in a continuous line, like a ribbon.

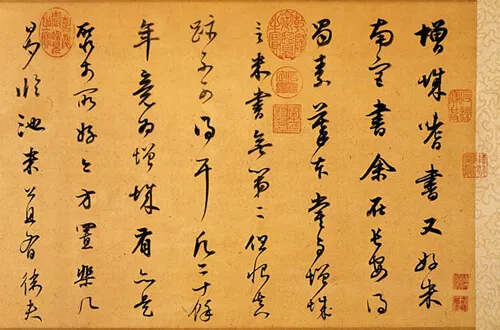

No. 7 On Sichuan Silk(蜀素帖)

- Author: Mi Fu (1051 – 1108)

- Date written: 1044

- Script Style: Running Script

- Size: 270.8 x 27.8 cm

- Where it is housed: National Palace Museum in Taipei

Mi Fu was a famous calligrapher, painter and poet. He was one of the four most respected calligraphers during the Song dynasty. The other three are Su Shi, Cai Xiang, and Huang Tingjian. His mother was emperor Shenzong’s wet nurse, so he was raised within the imperial premises, where he learnt calligraphy at the age of seven. Mi Fu found inspiration from masterpieces by calligraphers in the previous dynasties but added his own mark. He was so good that the standards he set served to rate calligraphers for the centuries to come. He believed in originality and criticized artists that failed to have personal expression.

On Sichuan Silk are 7 poems by Mi Fu himself. The unique quality of Mi Fu's calligraphy lies in the great variety, which derives from his excellence in making use of every potential with the brush. The strokes – regardless of whether the brush tip is concealed or exposed, or whether they are plump or thin – all express the beauty of the art of writing.

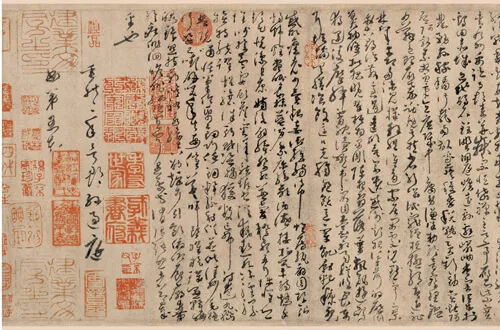

No. 6 Autobiography(自叙帖)

- Author: Huai Su (737 – 799)

- Date written: 777

- Script Style: Cursive Script

- Size: 755 x 28.3 cm

- Where it is housed: National Palace Museum in Taipei

Huai Su was a Buddhist monk and calligrapher of the Tang Dynasty (618-907). Zi Xu Tie, or Autobiography, is the representative piece of cursive style handwriting in Huai Su's late years. His writing looks like violent storms, which displays his own passionate nature. Legend has it that Huai Su was too poor to afford paper for his calligraphy practice. He planted banana trees in the courtyard of the temple where he lived and used the large leaves as paper to practice his art.

Zhang Xu (ca. 658–747), who was nicknamed “Crazy Zhang”, lived in the Tang dynasty. He is dubbed as the “sage of cursive style calligraphy”. Huai Su benefited from studying Zhang Xu’s style when he started working in the Cursive Style, but he created his own style as he became more experienced. One of the most noticeable differences between the two masters is that Huai Su’s strokes are much thinner than Zhang Xu’s.

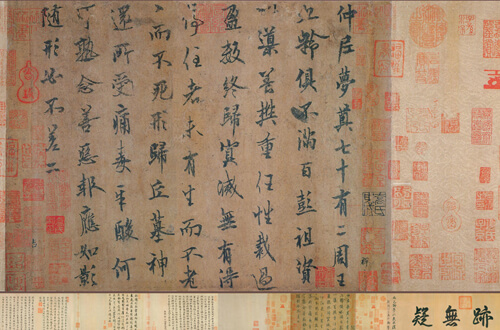

No. 5 In Memory of Confucius in Dream (仲尼梦奠帖)

- Author: Ouyang Xun (557 – 641)

- Date written: between 627 and 640

- Script Style: Running Script

- Size: 33.6 x 25.5 cm

- Where it is housed: Liaoning Provincial Museum in Shenyang.

Ouyang Xun was a renowned calligrapher, politician and scholar of the early Tang Dynasty. He is famous for his regular script known as "Ou style". His calligraphy was known for its sense of order and structure, and he is regarded as one of the Four Greatest Calligraphers of the Early Tang Dynasty. In Memory of Confucius in Dream is the masterpiece of his running script. It very much resembles the “Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion” of Wang Xizhi, which shows that Ouyang learned from Wang style but also had improvements of his own.

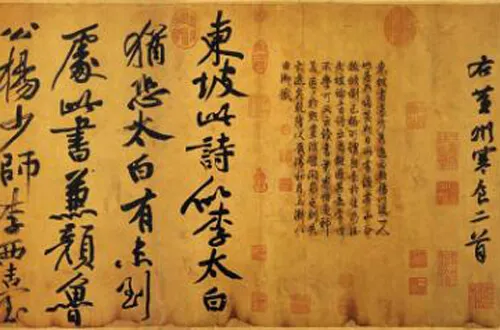

No. 4 Cold Food Observance(黄州寒食帖)

- Author: Su Shi (1037 – 1101)

- Date written: 1082

- Script Style: Running Script

- Size: 34.2 x 18.9 cm

- Where it is housed: National Palace Museum in Taipei

Su Shi, known also as Su Dongpo or by his given name Su Zizhan, is unlike other Chinese figures who are known primarily for their poetry or calligraphy or painting. He is a polymath. He excelled in writing, painting, calligraphy, and pharmacology, etc. In 1079, Su Shi was exiled to provincial Huangzhou, where he lived in relative poverty. He built a farm in the foothills of what became known as the Eastern Slope (Dongpo), and began to call himself Master of the Eastern Slope (Su Dongpo). For all the hardships he experienced in exile, it was during this period that he produced some of his most well-known verses. The Cold Food Observance, was written during his exile to Huangzhou in 1082, then later transcribed into a work of calligraphy. It is widely hailed as the finest surviving example of Su Shi’s celebrated calligraphy.

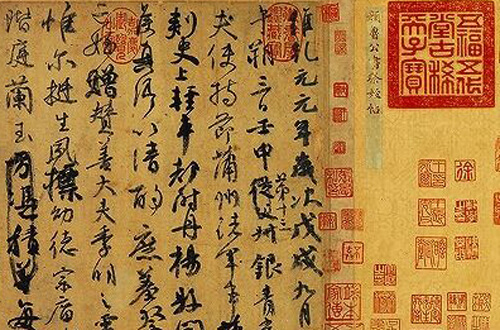

No. 3 The Draft of the Eulogy for Nephew Jiming(祭侄文稿)

- Author: Yan Zhenqing (709 – 785)

- Date written: 758

- Script Style: Cursive Script

- Size: 75.5 x 28.2 cm

- Where it is housed: National Palace Museum in Taipei

Yan Zhenqing was a court official and successful military commander in the Tang dynasty. He was best remembered as a famous calligrapher whose influence on the development of calligraphy proved to be as significant as Wang Xizhi’s. He created the “Yan Style” of regular script. During the An Lushan Rebellion (755-763), Yan Zhenqing’s brother Yan Gaoqing and nephew Yan Jiming were serving in the government of Changshan (modern Shijiazhuang). The rebel forces invaded the town, the Tang armies did not come to the rescue, resulting in the fall of the town and the death of Yan Gaoqing’s family of 30 people (including Jiming). Yan Zhenqing actually wrote this eulogy to all who were killed of his brother’s family. The enduring appeal of the Eulogy lies in the immediacy inherent in the draft form, the simplicity of the calligraphic manner, the monumental yet personal events it describes, and the emotion in Yan Zhenqing’s voice.

In 784, Li Xilie, the military commissioner of Huaixi, rebelled. Yan Zhenqing was sent to negotiate with Li Xilie. Even though Li Xilie tried by every means to coax or threaten him to surrender, Yan never wavered. For his refusal to serve under a rebel leader, he was hanged at the age of seventy-six.

No. 2 San Xi Bao Tie (三希宝帖)

-

Author:

Kuai Xue Shi Qing Tie by Wang Xizhi (303 – 361 CE)

Zhong Qiu Tie by Wang Xianzhi (344 – 386 CE)

Bo Yuan Tie by Wang Xun (349 – 400 CE) - Date written: 4th century

- Script Style: Running Script

-

Size:

Kuai Xue Shi Qing Tie: 23 x 14.8 cm

Zhong Qiu Tie: 27 x 11.9 cm

Bo Yuan Tie: 25.1 x 17.2 cm - Where it is housed: Kuai Xue Shi Qing Tie is in the National Palace Museum in Taipei and the other two are in the Palace Museum in Beijing

The Qianlong Emperor of Qing Dynasty was a grand patron of the cultural arts. To house the three most precious calligraphy works, a hall was built in Forbidden City under the emperor’s order, and it was called Sanxitang “Hall of Three Rarities”. The “Three Rarities” are referring to these three calligraphy works. Kuai Xue Shi Qing Tie is the only extant work by Wang Xizhi who is dubbed as the “Sage of Calligraphy.” Zhong Qiu Tie was written by his son, Wang Xianzhi. Along with his son, Wang Xianzhi, the Wangs were considered the greatest calligraphers in Chinese history whose achievements were insurmountable by later generations. Bo Yuan Tie was written by Wang Xun, who is Wang Xizhi’s nephew.

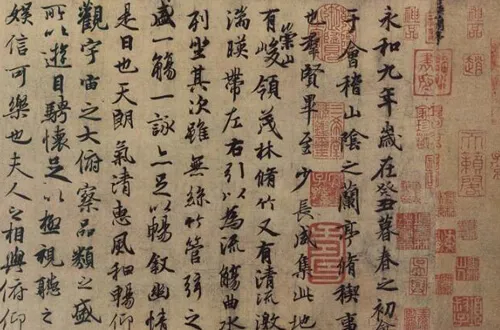

No. 1 Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion copied by Feng Chengshu(唐冯承素摹兰亭序)

- Author: Wang Xizhi (303 – 361)

- Date written: 353

- Script Style: Running Script

- Size: 69.9 x 24.5 cm

- Where it is housed: The original copy was said to be buried with the Emperor Taizong of the Tang Dynasty in his mausoleum. The copy by Feng Chengshu of Tang Dynasty is closest to the original copy. It is housed in the Palace Museum in Beijing.

Wang Xizhi was traditionally referred to as the “Sage of Calligraphy”. He excelled in every script but particularly in that of the running variety. Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion is a masterpiece by him produced at the prime of his calligraphy career (353). It is the best-known calligraphy piece in history. Legend has it that he wrote it after a drinking game, and he tried many times to a few days later to reproduce the Preface with the same quality, but he was never able to match his own incredible, spontaneous calligraphy.

Emperor Taizong of the Tang, who was a big fan of Wang’s calligraphy, personally collected nearly two thousand pieces of Wang’s work, and ordered a search for the original Preface. After acquiring it, he set it as a model for court officials and calligraphers to copy and study. When the emperor died, he ordered that the original Preface be buried with him. The emperor’s high regard encouraged later calligraphers to imitate Wang Xizhi’s style. The rubbings of the Preface today are mostly taken from imitations from the Tang dynasty, as the original was believed to be buried with emperor Taizong.

OR

Are you eager to begin your Chinese cultural journey?

Drop us a line and we will promptly connect you with our leading China expert!

Chinese Painting

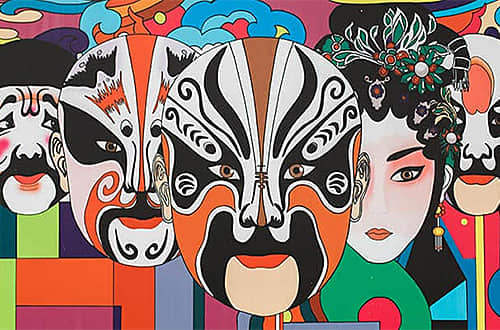

Chinese Painting  Beijing Opera

Beijing Opera  Chinese Kung Fu

Chinese Kung Fu  Chinese Music

Chinese Music