Chinese Calligraphy: A Concise Guide

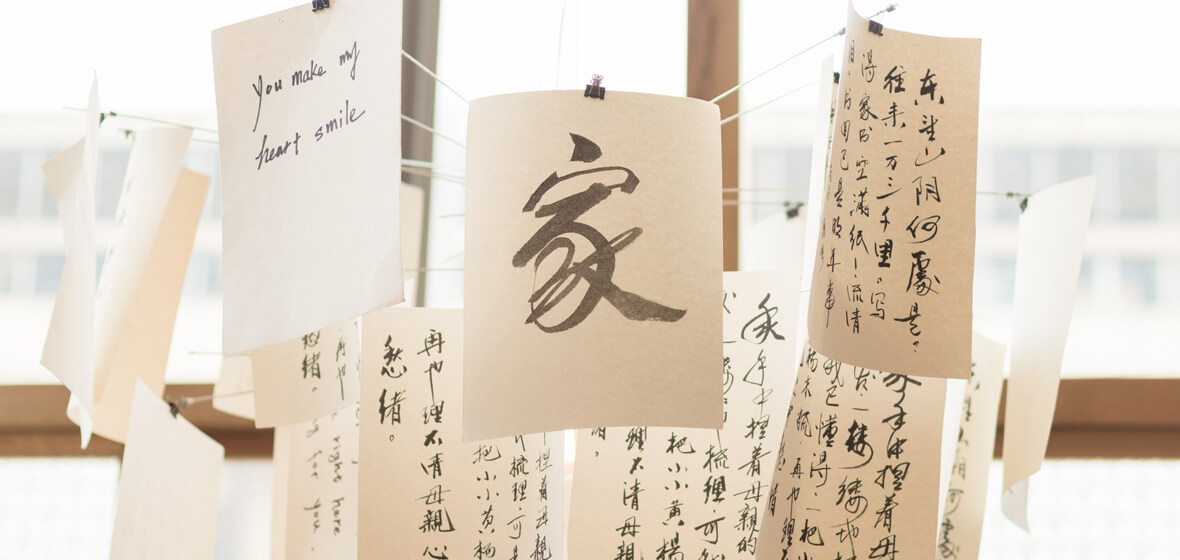

Chinese is one of the few languages in which the script is not only a means of communication but is also celebrated as an independent form of visual art. ‘Shufa’ 书法, or Chinese Calligraphy, was the paramount visual art in pre-modern China. Using only brush and ink, calligraphers developed their techniques over generations. The earliest surviving Chinese script dates back over 3,000 years, in inscriptions made for the rulers of the Shang dynasty (circa 1600 – 1100 BCE). Since the fourth century CE calligraphy has been practiced, prized, and collected as an elite visual art. From as early as the 10th century calligraphy was a key component of the imperial civil service examinations. Honing your writing could pave a path to power and prestige. Collectors and connoisseurs also saw exceptional calligraphy as an expression of upright morality. Good character was seen in good brushwork.

Calligraphy originally had a more practical than aesthetic purpose. It was intended to express the written form in a correct, legible, concise and contextual manner. The aesthetic part, by no means unimportant, came next. To be a good calligrapher, one needed not just a well-honed skill with the brush, but also a deep knowledge of various artistic, cultural, social, political and philosophical matters.

According to an old Chinese saying, "the way characters are written is a portrait of the person who writes them." Expressing the abstract beauty of lines and rhythms, calligraphy is thus a reflection of a person's emotions, moral integrity, character, educational level, accomplishments in self-cultivation, intellectual tastes and approach to life.

1. What Tools Are Used to Write Chinese Calligraphy?

“The Four Treasures” are the most essential implements for any calligrapher. They are the brush, the paper, the ink stick, and the ink stone.

The brushes can be made from animal hair or synthetic fibers; however, it is widely agreed that using a brush made from the tail hair of a skunk is considered to be best. Soft brushes are typically made of sheep hair.

For paper, traditional rice paper (also known as Xuan paper) is the preferred choice. Soft, flexible and smooth, rice paper can absorb ink very well. The rice paper was traditionally produced in Xuancheng in eastern China’s Anhui province. Hence it was called Xuan paper. Traditional black ink stick color comes from the soot from charred pine tree roots, specifically Masson pine (Pinus Massoniana) in the Yellow Mountain area. Nowadays liquid ink is also widely used.

An ink stone is used to make liquid ink for calligraphy and painting, by grinding an ink stick while mixing it with water. The four most famous ink stones in China are the She ink stones in Anhui Province, the Duan ink stones in Guangdong Province, the Tao ink stones produced in Gansu Province, and the Chengni ink stones in Shanxi province.

2. What are the Five Main Script Styles in Chinese Calligraphy?

According to Chinese legend, Chinese writing was invented by Cangjie, who lived in the 27th century BCE and conceptualized the notation of simple images to represent objects. Cangjie was inspired by the footprints of animals and birds in the sand, and he devised a system of notation that became early Chinese writing. While the earliest use of script has been dated to the Longshan Era of the Neolithic period (c. 2500 – 2000 BCE), paleographers and archeologists have traced early Chinese logographs to a form of script engraved on tortoise shells and the larger bones of animals, which is believed to have been widely used in the Shang Dynasty (c. 1600 – 1046 BCE). This script is known as jiaguwen, also known as shell-and-bone script or oracle bone script, as many of these scripts referred to ancient divination rituals, mystical prognostication, or religious themes. Over time, 5 main script styles in Chinese Calligraphy were developed, and there are hundreds of sub-styles. The 5 main script styles are:

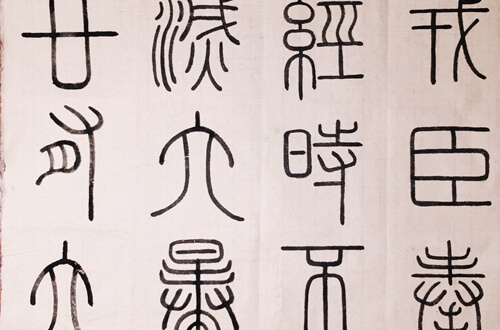

Seal Script (zhuanshu 篆书)

Seal Script was developed in the Zhou Dynasty (1046 – 256 BCE) and was adopted as the final script for all of China during the Qin dynasty (221 – 206 BCE). The script was widely used for decorating and engraving purposes during the Han Dynasty. It belongs to the Bronze Age of China and is logographic in nature. Seal Script took the form of pictograms and ideographs, and was incised onto surfaces of jade and oracle bones, as well as surfaces of ritual bronze vessels. Today, this style is used predominantly in seals (called 'chops’).

Clerical Script (lishu 隶书)

The Clerical Script appeared in the Qin Dynasty (221 BCE – 206 BCE) and was used by government clerks. In the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), flexible hair brushes came into regular use, their supple tips produced effects that were not attainable in incised characters in the Seal Script. This style is still in use today, making it the longest-lasting script from ancient times to the present day. Generally, this type of calligraphy is reserved for official seals and stone inscriptions.

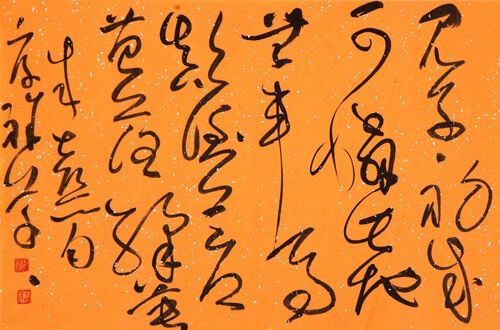

Cursive Script (caoshu 草书)

The Cursive Script originated in the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE) when it was used for daily correspondence between friends and family members. This writing style imitates people’s handwriting in everyday life. The strokes are typically curved or slanted, and a single character can be written in different ways. As a fully cursive script, characters in the Cursive Script with drastic simplifications require specialized knowledge to be recognized.

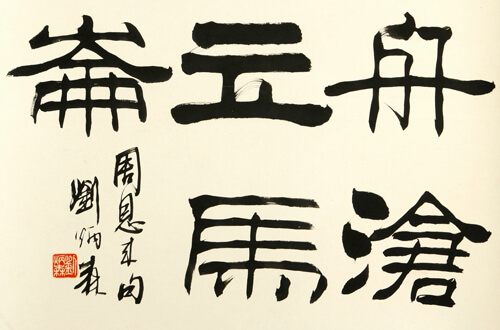

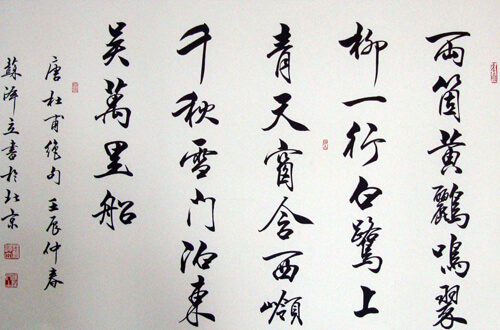

Running Script (xingshu 行书)

Running Script (also called "semi-cursive script") developed in the Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE). This style is fast and easy to write. It was designed for the common writer who had no time or patience to read and write the clerical script.

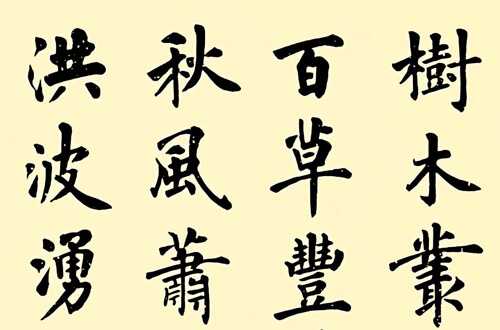

Regular Script (kaishu 楷书)

Regular script is also known as “uniform script” and “real script”, referring to a typeface of order. Regular script is a regular typeface directly evolved from clerical script. It was developed during the late Han Dynasty (206 BCE – 220 CE), gaining momentum in Wei-Jin North and South dynasties (220 – 581 CE) and reaching its prime in the Tang dynasty (618 – 907 CE). Regular script is utilized by the Chinese today in modern writing, and is used for printed books, government documents, and important papers.

3. Who are the top 10 most famous calligraphers in China?

There were many famous calligraphers over the 2000 years of history. We have listed 10 of the most famous ones below:

1. Wang Xizhi 王羲之 (c. 303 – c. 365 CE)

Wang Xizhi is the most revered of all Chinese calligraphers. He helped develop various forms of calligraphy such as the regular script, cursive and semi cursive script that continue to influence many generations in China and beyond. His work Preface to the Poems Composed at the Orchid Pavilion is considered the greatest masterpiece of Chinese calligraphy in history. Another famous work is ‘Kuai Xue Shi Qin Tie’ (Timely Clearing After Snowfall).

2. Ouyang Xun 欧阳询 (557 – 641CE)

Ouyang Xun’s calligraphy was known for its rigorous and grand strokes as well as its unique order and structure, and was called "Ou Style" by later generations. He is regarded as one of the Four Great Calligraphers of the Early Tang Dynasty. The masterpieces by Ouyang are ‘Jiucheng gong Liquan Ming’ (Inscription on the Sweet Spring in the Jiucheng Palace) and ‘Zhang Han Tie’ (Zhang Han Manuscript).

3. Yan Zhenqing 顏真卿 (709 – 784CE)

Yan Zhenqing was a notable calligrapher and a governor of the Tang Dynasty (618 – 907). He mastered Regular script as well as Cursive script but was famous for his "Yan" writing style of Regular script. His style is still taught today as a standard Regular script and Chinese bookstores the world over stock inexpensive reproductions of his works for sale as copybooks. Yan's calligraphy is reflective of his upright, brave and aboveboard life. The masterpieces by him included Record of Duobao Pagoda Stele and Draft of a Requiem to My Nephew (Ji zhi wen gao).

4. Zhao Mengfu 赵孟頫 (1254 – 1322 CE)

Zhao Mengfu is a pivotal figure in Chinese art history. He was good at both Chinese painting and calligraphy. Zhao was adept in many styles of calligraphy, such as seal character, official script, running script and the cursive script, and he also created his own style, Zhao Style. Aside from his own high achievements, Zhao also emphatically called for the change of calligraphic style by learning from ancient models and the application of calligraphic principles to painting. Zhao exerted a significant influence on the calligraphy circle of the Ming and Qing dynasties (1368 – 1911). His masterpieces included Odes to the Red Cliff, Danba Bei and Luoshen Fu.

5. Liu Gongquan 柳公权 (778 – 865)

Liu Gongquan stood with Yan Zhenqing as one of the two great masters of late Tang calligraphy. Liu’s works were imitated for centuries after and he is often referred to in unison with Yan Zhenqing as "Yan-Liu". He first learned the handwriting of Wang Xizhi. As he read more calligraphic books closer to his time, he switched to the handwriting of Yan Zhenqing and blended into it his own creative style. His characters are of moderate build, not as slim as those of the early Tang Masters or as chubby as those of Yan Zhenqing. His masterpieces include Xuanmita (Mysterious Pagoda) Stele and Vajracchedika-sutra.

6. Wang Xianzhi 王献之 (344 – 388 CE)

Wang Xianzhi is the son of Wang Xizhi, and they were known as "Er Wang” (Double Wangs). Wang Xianzhi was accomplished in writing cursive script and official script. His masterpieces include Luo Shen Fu (also known as Yuban Shisan Hang) and Zhongqiu Tie.

7. Su Shi 苏轼 (1037 – 1101)

His art name is Dongpo, so he is also known as Su Dongpo. As a poet, politician, writer, calligrapher, painter and aesthetic theorist, Su Shi was the pre-eminent scholar of the Northern Song dynasty (960 – 1127). He is recognized as one of the four Song masters of calligraphy. He formed his own distinctive and unique calligraphy theory after Wang Xizhi and Wang Xianzhi, and became the representative of traditional literati calligraphers with superb literary accomplishment and unique calligraphy art. The Cold Food Observance is his masterpiece.

8. Dong Qichang 董其昌 (1555 – 1636)

Dong Qichang was not only a noted Chinese landscape painter, but he was also a great calligrapher. At the age of 12 he took and passed a civil service exam where he won a place at the Government School. At 17 he took the imperial civil service exam, however he was placed second because although he was bright, his calligraphy was messy. Being a perfectionist, Dong spent the next few years training to become a famous calligrapher. Studying the past plays a central role in Chinese calligraphy and even as one develops a personal style, it is necessary to revisit the old masters to discover new insights. Dong studied the works of eminent calligraphers like Zhao Mengfu, Wen Zhengming and other masters of the Jin and Tang dynasties. In emulating archaic calligraphic methods, Dong Qichang's semi-cursive calligraphy illustrates his characteristic expressive simplicity and even elegance.

9. Zhang Xu 张旭 (710 – 750)

Zhang Xu was well known for his explosive cursive script, but he also excelled in the regular script. Anecdotes go that he grasped the essence of cursive writing by observing some porters fight for their way with the guard of honor of some princess, and by watching the solo performance of a famous sword-dancer. He was known as a sage of cursive script. It can be said that it was Zhang Xu and Huai Su (a monk calligrapher) who created and perfected the art of explosive cursive script. His masterpieces are Gushi Sitie and Shiwuri Tie.

10. Mi Fu 米芾 (1051 – 1107)

Mi Fu was a famous Chinese calligrapher, painter and poet. He was one of the most respected calligraphers during the Song dynasty. Mi Fu always pursued his own style. He introduced the aesthetic ideal of pursuing true interest into the composition of calligraphy. His signature works included Yan Shan Ming, On Sichuan Silk, and Poem Written in a Boat on the Wu River.

4. What are the best places to view Chinese calligraphy during my trip to China?

Each day in many parks around China, one can encounter senior citizens drawing beautiful calligraphy on the pavement with nothing more than a bucket of water and a long, broom-like brush. Fluid, elegant characters appear all too briefly, vanishing as the water dries.

Here we have listed some of the best places where you can view Chinese calligraphy during your trip around China:

Xiling Seal Engraver's Society in Hangzhou

Originally established in 1904, Xiling Seal Engravers’ Society (西泠印社) in Hangzhou is an association devoted to seal arts, the study of inscriptions on bronze and stones. In 2009, Xiling Seal Engravers’ Society was listed as a World Intangible Cultural Heritage. It has made great achievements in cultural relics collection and study, edition and publication, international cultural exchange, and other fields. The society is located at the foot of the west side of Gushan Hill (The Solitary Hill) in Hangzhou, extending to Bai Causeway linked to the east shore and to Xiling Bridge linked to the north shore. The sigillography museum houses a large number of calligraphy and carving pieces.

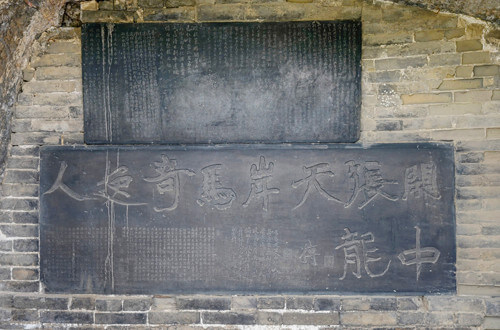

Stele Forest in Xi’an

The Stele Forest is a museum which mainly displays works of calligraphy, painting and historical records. The museum, which is housed in a former Confucian Temple, has housed a growing collection of Steles since 1087. It is a place of collection of treasures of calligraphic art of all dynasties. It is also the source and foundation of the art of calligraphy in China. Altogether, there are 11,000 steles in the museum, which is divided into seven exhibition halls. The key highlights of the collections include Duobao Pagoda Stele and Yan qinli Stele by Yan Zhenqing , Xuanmita Stele by Liu Gongquan and Cao Quan Stele by an anonymous calligrapher. It also includes the Nestorian Stele, erected in 781 which, in Chinese and Syriac, recorded the arrival in 635 of the Christian bishop Alopen.

Longmen Grottoes in Luoyang

The Longmen Caves, or Longmen Grottoes, near Luoyang, China, are a series of approximately 2,000 caves containing in excess of 100,000 stone carved Buddhist statues, some dating back as far as the 5th century. The Longmen Caves are today a UNESCO World Heritage site. Besides the beautiful stone statues, it is also the best place to view Wei Stelae Style calligraphy. The Wei Stelae Style is a transitional style; it borrows from both clerical and regular characteristics. The characters are moderately flat and wide (less so than the clerical style) but appear tall (similar to the regular style). Another feature is its series of angular strokes.

In Guyang cave, the oldest cave at Longmen, over 800 inscriptions are contained within the cave, making it one of the richest at Longmen and significant as a reflection of the late Northern Wei style of writing. Inscriptions attached to statues within Guyang Cave include 19 of the 20 inscriptions designated as exemplary forms of Northern Wei calligraphy and are critical in helping to identify the origins of each work.

Qian Tang Zhi Zhai – Epitaph Museum in Luoyang

The museum was grown from the private collection of Zhang Fang (1886 – 1966), who served as governor of Henan province in the 1930s. Zhang loved the steles and calligraphy very much. He began to extensively collect epitaph stone carvings in 1931, as well as steles, and successively transported them to his hometown, Tiemen Town near Luoyang. There are 1578 pieces of epitaph stones, 1191 of them are from the Tang Dynasty, and hence it was called “qian tang zhi chai”, a museum which houses one thousand pieces of Tang Dynasty stelae.

Qian Tang Zhi Zhai is a treasure trove of historical materials for the study of history, culture and calligraphy art in the Tang Dynasty.

The Orchid Pavilion Garden in Shaoxing

The Orchid Pavilion Garden is located in the southwestern suburbs of Shaoxing. The garden is believed to be the place where Wang Xizhi invited 41 like-minded literati gentlemen to hold a gathering in the spring of 353 CE. After the gathering, they compiled a collection of poems which were the poems they had composed during the gathering. Whereas the poems that were written at the Lanting Gathering have mostly been forgotten, Wang Xizhi's "Preface to the Poems Collected from the Orchid Pavilion" became very famous. It was touted as the top calligraphy in Chinese history. The original writing has unfortunately been lost but multiple copies still exist, either as ink-on-paper copies or stone inscriptions. You can find copies in the calligraphy museum here. One of the pavilions, the Imperial Stele Pavilion, is a magnificent structure with beautiful woodwork and rich stone carving. The calligraphy was written by Qing Dynasty Kangxi and Qianlong.

The Evolution of Chinese Characters

The Evolution of Chinese Characters  Chinese Painting

Chinese Painting  Chopsticks: Everything You Need to Know About Chopsticks

Chopsticks: Everything You Need to Know About Chopsticks  Top 5 Origin Place of Kungfu

Top 5 Origin Place of Kungfu